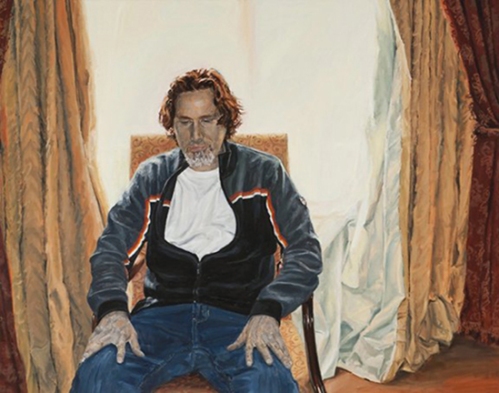

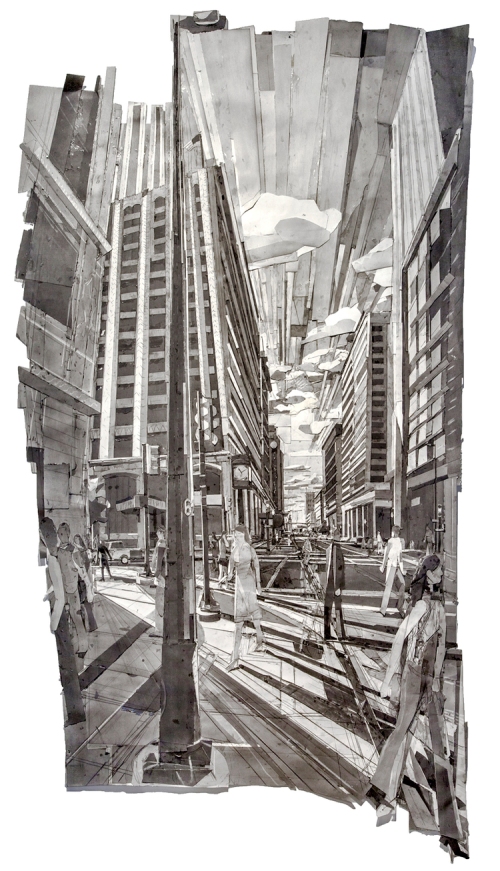

Kathy Liao, “Growth (drawing)”, 2015, mixed media, 58″ x 42″

The Borders of Itself is an exhibit I put together for the Campanella Gallery at Park University in Kansas City. The exhibit includes artists Kathy Liao , Misha Kligman, Damon Freed and Stephanie Pierce .

The title of the exhibit is taken from the last stanza of the R.M. Rilke poem, “Archaic Torso of Apollo”. Rilke’s sonnet is drawn on a sustained and thoughtful look at the eponymous sculpture housed in the Louvre, written after getting some advice from the sculptor August Rodin. Rodin’s advice: write less about insubstantial and ephemeral inner moods and try to ground one’s words in the real and material world.

installation view of Misha Kligman, “Closeness”, 2016, flashe on canvas, 67 1/2″ x 47 1/2″

That idea of an artwork that exists as a cooperation between material and idea is really appealing to me. That’s what we learn to do as painters, right? Not master or control or force our materials to submit to our will,–no, we learn to work with the properties of paint and pigment. That seems to me an incredibly contemporary idea–to cooperate with, rather than master or rebuff, the physical world.

When Rilke looks at his archaic torso closely, he realizes this immobile fragment of marble tells stories. Not just A STORY about a long since de-deified mythological character, but many complimentary stories, layered and simultaneous. Yes, the character of Apollo is a story. Then too, the unknown sculptor, and the very act of making this statue, is a story. What drove this artist, what goals, standards and values did he apply to the making? What accidents and learning occurred through the process of making? It can’t be forgotten that the long life of this ruined fragment is a story. And of course, the way these forms act upon the viewer is a story–and the poem is loaded with various excitations, arousals and meditations the physical presence of this storied object elicits in young Rilke.

installation view of Damon Freed, “Chapter XII: Infinity Shape”, 2016, oil, acrylic and ink on canvas, 34″ x 34″

To me, that’s what all these works have in common: layers of histories and stories. Some of those stories seem to be depicted in the paintings. Some of these stories are made as the paintings are made, in every action and every decision the artist makes (this is the reason so many of these paintings heavily telegraph the artist’s process). Some of these are stories about the artists’ relationships to their source material–whether that be memory, observation, photography, or drawing. Some of these stories are about the physical, phenomenological relationship between the painting-object and the viewer-subject.

Stephanie Pierce, “Long Lapse”, 2014, ink, vellum, graphite on paper, 18 1/2″ x 17″

Stephanie Pierce, “Discordant Wave”, 2014, ink on paper, 13″ x 14″

Spending some time with these works it’s occurred to me that another common thread is a distressed relationship between simple Figure and Ground. In Stephanie Pierce’s drawings, layers and layers of words overfill the page around a simple image of a radio, allowing the negative space to be neither peaceful nor lonely. Layers of differently-intentioned painting keep the background in Kathy Liao’s painting from settling into a passive role relative to the massive snake plant in the foreground. Misha Kligman uses four drippy disembodied arms to frame a grid of close-value queasiness that threatens to overwhelm what appears to be a shock of long blond hair. Damon Freed pushes hard edged negative shapes that appear to sit on top of the thinly painting figure/forms. Figure and ground can be a simple relationship and all of these complications start to seem like alternate versions of Rilke’s strategy of choosing a headless torso. So many of the best metaphors do spring from a flawed protaganist–whether that be the headless torso of Apollo, one-legged Capt. Ahab, nearly-blind Beowulf or Saleem Sinai and the various deformities Salman Rushdie inflicts upon the character in Midnight’s Children.

In the paintings the distressed figure/ground relationship is a tragic flaw that increases both the romantic appeal and the metaphorical depth. When we, the audience, acknowledge that the Other has stories and histories and struggles–many, many layers of stories and histories–we start to engage in the process of understanding that Other.

installation view of two paintings by Damon Freed, on the left is “Chapter XIII: Angel”, 2016, oil, acrylic and ink on canvas, 34″ x 34″ and on the right, “Chapter XIV: Mother, Father and Holy Ghost”, 2016, oil, acrylic and ink on canvas, 34″ x 34″

Lately it seems like one can’t be in a room with other artists without someone starting to talk about empathy. We live in a culture of easy dismissals, of easy “Likes” and crass comments, and on those occasions we do try to engage, we’re all vulnerable to being overwhelmed by images of refugees and stories of brutality, hurt and loss. Making empathy plausible–or, re-sensitizing we, the de-sensitized–is one of the more compelling missions undertaken by contemporary art. “Archaic Torso of Apollo” speaks out of the past to these contemporary concerns by ending, abruptly, with the words: “You must change your life.”

That’s what Empathy really asks of us, to sustainably adjust one’s thoughts and actions to the acknowledgement of an Other. We have to see that both objects and people we encounter are, yes, for a moment, a part of our story, and at the same time, stories and histories of their own. Further, we have to be able to maintain that feeling over time. In thinking that paintings might be a useful tool put toward this goal, I’m reminded of Susan Sontag in “Notes on Style” addressing art as a nourishment for our moral faculties as well as the story Lawrence Weschler recounts of the war crimes tribunal judge who restores his peace of mind with a daily visit to the Mauritshuis to see the Vermeer paintings there.

When I have the opportunity to put together exhibits, it’s always my hope that the theme is applied lightly. The viewer should be able to simply enjoy the artworks for all their own reasons. There’s a thread tying these works together, an idea that I think is worth thinking about, and an idea that allows the artworks to offer their own stories.

installation view of works by Kathy Liao, Misha Kligman and Stephanie Pierce

I want to thank the artists for being involved in this show, as well as Park University and the gallery directors I worked with–Matt LaRose and Dr. Andrea Lee. Not possible without these individuals. To see more MWC Curatorial efforts, look here.