Christina Renfer Vogel‘s exhibition Home Bodies is on view at the Christensen Art Center at Augsburg College, Minneapolis, MN, through March 23, 2017. She lives and works in Chattanooga, TN, where she is Assistant Professor of Painting and Drawing at University of Tennessee Chattanooga.

What have you been working on lately?

I spent 2016 transitioning from a body of work that depicts figures in groupings and gatherings, isolated within fields of color. I worked from snapshots as a starting point for this work because I was interested in the chance encounters and awkward compositions that resulted from the casual images. While I am still connected to these paintings, I was ready to move on, feeling the itch to work from life again.

In June 2016, I attended a residency at the Hambidge Center for the Creative Arts, located in Rabun Gap, Georgia. It is an incredible place. I had a small cabin that served as both my home and studio for two weeks. Surrounded by trees, and without easy access to cell phone reception or the Internet, I was in walking distance to hiking trails and waterfalls. My time there served as an intense period of quiet and productivity. I wanted to respond to the specificity of this place, so I made small paintings in and around my cabin, working from the verdant surroundings and lean interiors. I wouldn’t really say that I made landscape paintings, but it felt exhilarating and challenging to work through the problem of interpreting the landscape. It is so complex! I was moved by the color and by the fullness of it all up against the sparseness of the cabin. It felt like Bonnard’s painting with the yellow mimosa, about to burst through the window, but in green.

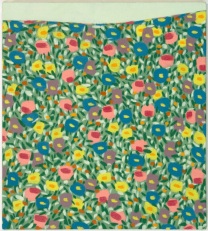

Back in the studio, I have been making paintings of houseplants. I am still working through my motivations for this work, but it is certainly rooted in my interest in portraiture (the plants act as surrogates for figures) and still life. Like working from the landscape, plants serve as a vehicle for me to build a painting in a new way, offering unexpected and complex visual information that is pure pleasure to translate through painting. I have paired the plants with patterns in some cases, thinking about the kind of pattern of these living things that extends to decorative backdrops. It connects to my figurative work in some ways; solitude or stillness is still a part of it in a way, but it is also a departure. After making paintings with so much space and psychological tension, I wanted to swing in another direction and make work that felt abundant. I am also occupied with t he unremarkable, so there is something about the everydayness of houseplants that draws me in. I see potential for a kind of theatricality through staging these tableaus, balanced with a directness that I like to offer through my work. I think it also speaks to my traditional studio-based painting practice; I am bringing all these things from the outside in, filling my space and translating my encounters. The beginning stages of this new work are on view now in a solo exhibition, Home Bodies at Augsburg College in Minneapolis, which runs through March 23.

he unremarkable, so there is something about the everydayness of houseplants that draws me in. I see potential for a kind of theatricality through staging these tableaus, balanced with a directness that I like to offer through my work. I think it also speaks to my traditional studio-based painting practice; I am bringing all these things from the outside in, filling my space and translating my encounters. The beginning stages of this new work are on view now in a solo exhibition, Home Bodies at Augsburg College in Minneapolis, which runs through March 23.

One other thing about working elsewhere for a while is that you can come away with insights about your usual working environment. Did that happen after Hambidge? Does place affect your work significantly? If yes, how so?

Working at Hambidge felt so natural and easy, and I think that it was a result of being largely unplugged, with generous stretches of solitude. I have a great Chattanooga studio, but the periods of uninterrupted time and space I experienced at Hambidge is not something I can recreate in my daily life. I like that my studio is apart from my home—something about going to work that works best for me—but the live/work experience while I was in residence resulted in great productivity. Residencies show me that I work best when I have long stretches of time. That’s simply not possible at home, especially during the academic year. I still maintain my studio practice, but it becomes necessary to work in fits and starts, around life and teaching responsibilities. The magic of residencies is the opportunity to engage with a fully immersive studio experience. Residencies always remind that time is so critical.

Although it has not always been at the forefront, I think place does affect my work, because I am always responding to the world around me in some form. At Hambidge, I worked in response to my surroundings, so place drove the work in a direct way. Right now, I am thinking more about creating environments within my studio, in a way, which is a different approach to the idea of place.

I’m curious about the engagement of the “unremarkable.” In looking at these newest paintings, it seems the mark itself has acquired a different kind of ease and abandon, and the tension now is more formal-visual: the relationships between a shape and the working space, a foregrounded object and backgrounded pattern, or variable levels of “finish” co-existing in the same painting. How does the more intimate scale function in this work? Is it a kind of challenge, or hurdle? Is it a comfort?

I think your observation is right on, that the tension is now less psychological and more formal. I am aiming for a kind of visual excess. The fullness of some of the work is juxtaposed with openness in other paintings such as a plant on a table without adornment. The intimate scale of the interior/exterior paintings contribute to a sense of stillness, I think, but the size also encouraged me to work more quickly and fluidly, too. The most recent paintings of plants and patterns are about life size and a bit larger, so there is a scale shift. I think intimacy may come into play regarding my exchange and encounter with a subject. Houseplants are domestic objects, and the patterns are taken from pillowcases and tables cloths in some cases. Maybe those hints of domestic life contribute to a kind of intimacy as well.

You mentioned Bonnard—are there other painters who figure in prominently/consistently in your own approach?

I am not always thinking about specific painters in relationship to the work I am making in a direct way, but I have thought about Bonnard and Vuillard in response to working with pattern. I am wild about how both artists use color and mark, of course, but I am also specifically thinking about the way they filled the space of their paintings. I appreciate you saying that there is a different kind of ease in more recent work, because that is always something I chase after. I find that I am continuously drawn to painters who do more with less and who make work that feels effortless. My favorites include Morandi, Fairfield Porter, Alice Neel, and Lois Dodd, painters committed to the experience of looking but who navigate that space between seeing and describing with decisiveness and invention. Painters like Amy Sillman, Clare Grill, and Katherine Bradford might be less obvious in relationship to my work, but they are some current artist crushes.

Are there any “known unknowns” in the work right now? Things you expect to discover through the work, or things you find yourself painting into without expectation but with some frequency?

I always feel a sense of the unknown when I work, which is why I make paintings, I think. I often make drawings alongside my paintings, but I don’t usually make sketches or plan much before starting. Instead I like to dig in and work it out through painting—at least that is the hope. There is a lot to be discovered through making, and searching for a resolution or solving a problem through the work is what makes the whole process worthwhile, for me. If painting was simply about executing a preformed idea, it would not be satisfying. It is a bit difficult to articulate, but I think the “known unknown” is the search for a stopping point. That is one of the fundamental questions for painters, right? Guston wrote about this and the idea that to stop a painting is always a kind of compromise. When I ask myself what I hope to discover it has to do with formal resolution and discovery, such as how to approach surface or wrestle with materiality or color, but it is also tied to working through content. Related to this idea of doing more with less, I suppose I’ve also been asking myself “how much does it need?” My relationship to my work deepens and changes over time, but I am at a point now where things feel new and pliable in an exciting way.

A familiar, two-part MWC question: what is some advice that you were given early on that has continued to ring true? What is something equally true that you’ve had to learn for yourself?

I don’t remember ever getting this as a piece of advice, per se, but the painters I have admired ever since I was a student, my professor mentors and peers, modeled the importance of pursuing the work and ideas they were passionate about rather than chasing after current trends. This was important when I started to get serious about my developing practice, and it still resonates. I find my interests are in line with what Mira Schor would call “modest painting,” which is usually not the cool thing.

I think the most important truth for me in regards to my professional life, and what has allowed me to sustain my practice, was to learn to respect my studio time as work time. My painting practice is the most rewarding and challenging job, but it is still work. It is not my only job, and I am so fortunate to have a teaching position that creates a kind of exchange with my practice, but that does require me to carve out dedicated studio work time. This requires commitment as well as a degree of sacrifice at times, because it does cut into my personal life, but it is how I am able to keep my practice going. That is something I really had to experience and learn for myself once I was out in the world navigating professional life.

Thank you Christina!

Works: Night Light, 2016, oil, acrylic, and Flashe on linen, 46 x 46 inches; Front Porch,

2016, oil and acrylic on panel, 8 x 10 inches; Threshold, 2016, oil on linen, 42 x 48 inches; In Bloom, 2016, oil on canvas, 30 x 24 inches; Tiny Floral, 2016, oil on canvas, 16 x 14 inches

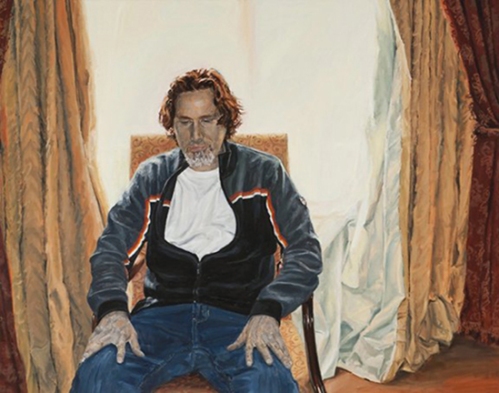

rbrush, really tangly. One winter afternoon I saw a hill covered with bare trees that was bathed in orange sunlight, and it looked like the hill was covered in glowing orange hair. Ever since then I’ve been enamored of light interacting with live or dormant vegetation and hair. Since I think of the portraits as personifications of this region, it made sense to amplify that connection between hair and foliage.

rbrush, really tangly. One winter afternoon I saw a hill covered with bare trees that was bathed in orange sunlight, and it looked like the hill was covered in glowing orange hair. Ever since then I’ve been enamored of light interacting with live or dormant vegetation and hair. Since I think of the portraits as personifications of this region, it made sense to amplify that connection between hair and foliage. Working with Dax reintroduced me to the importance of working from the gut…reacting. It also introduced the new element of real surprise, as neither of us knew what the other was going to paint or how they would react to what had been painted.

Working with Dax reintroduced me to the importance of working from the gut…reacting. It also introduced the new element of real surprise, as neither of us knew what the other was going to paint or how they would react to what had been painted.